By Doug Larsen

Copyright 2013

In 1984, Ronald Reagan was President of the United States. Madonna was a controversial twenty-something pop star as she performed her hit, “Holiday” on American Bandstand. The blockbuster movie of that year was Ghostbusters, and it was no big deal to drive to the theater to see it, gasoline was a buck a gallon.

Oblivious to the political and social activity over 6000 miles away in the United States, a woman in Rio Grande, Tierra del Fuego, the tiny island separated from the larger land mass of Argentina by the infamous Straits of Magellan, had been listening to the opinions of several respected Argentine anglers. Based upon their recommendations she was in the final stages of completing a plan. A year or two after the end of Argentina’s disastrous and bumbling war for the Falkland Islands (just a few hundred miles offshore of Tierra del Fuego) she was about to launch a fishing lodge on the Rio Grande, where she and her family owned land along the river. She proposed to introduce the sport fishing world to the huge sea run trout of Tierra del Fuego.

While salmon angling trips to Iceland and trout fishing vacations in New Zealand are seen as commonplace among today’s discriminating global angler, in 1984 fly fishing travel was in it’s infancy. Sea run trout were known only to the British, the Norwegians, and to a few knowledgeable local estancieros in Tierra del Fuego. The few others that knew about the fishery were the well-traveled fly-fishing illuminati of the time–the likes of Joe Brooks, Jorge Donovan, and Juan “Bebe” Anchorena. They had insider information about the big trout, because ranching family members knew that the fish that had been planted there in1935 by John Goodall had grown, gone to the sea, and were returning regularly each year as brutish trout in the 10-15 pound range.

To bring trout anglers thousands of miles to fish largely untested waters seems, in hindsight, like a pipe dream. But Jacqueline de las Carreras had faced adversity in her life and was not the kind of individual that was told that something could not be done. Her family, landed gentry from Buenos Aires, owned thousands upon thousands of acres of grazing land on the island of Tierra del Fuego. They had been grooming Jacqueline to be one of Argentina’s noted socialites during the Peron years, but after she was stricken with polio at age 15 during the polio epidemic of 1950, (it would be two years later that Jonas Salk would create the polio vaccine) she was to be confined to a wheelchair. But from that wheelchair, Jacqueline meticulously planned a luxurious wood-paneled lodge to be larger than most suburban homes. Never mind the fact that she had no prior knowledge of fishing or lodges. She had never wet a line in her life-had never set foot in a fishing lodge, yet she set out to build the most exotic fly fishing destination of the time. She would be a socialite after all, but the world was going to come to her.

Building such a thing as a large fishing lodge in Tierra del Fuego seemed an impossibility-there are no trees to speak of on the island, and thus lumber is in short supply. Virtually every building on Tierra del Fuego is made of concrete block, and is an architect’s ugly nightmare. This was not to be for Jacqueline. Kau Tapen, or “fishing house” in the native Ona tongue, was hand constructed in San Carlos de Bariloche from Andean cedar, then shipped in modular fashion; hauled in a procession of trucks some 2000 miles where it was reassembled and capped off with a smart green, tin roof. The lodge would rest on the crest of a small knoll just off the Rio Grande river, and overlooking the smaller Rio Menendez. Behind the lodge was a generator shack, and in the front garden, fenced to keep the sheep from grazing on a patch of newly planted grass, three tiny, rented Fiat sedans, the cars that would be used to take anglers to the river.

Kau Tapen opened for business in 1984, with Jacqueline Carreras serving as the hostess alongside her long time aide Betty. She employed a grumpy chef, and a waitress from nearby Chile, and brought in three guides. I came from Minneapolis, by way of Alaska where I had been guiding for several years. I knew how to fish trout and pacific salmon, but I knew nothing of sea trout. My only real qualification for being there was the fact that I had not slept through many high school Spanish classes. However it became instantly apparent to me that Spanish learned in a public high school in Minneapolis, while useful in a Cancun taxi, was woefully inadequate for the intelligent, articulate, Spanish speakers I met in Argentina. I struggled from the minute I arrived. I had however brought along a copy of Hugh Faulkus’s book, Sea Trout for ready reference. I had read some of it on the airplane. Mostly it was about British anglers sneaking around in the dark, casting two and three fly traces into small streams with an open loop, while trying to catch sea run trout out from underneath streamside brush. The book had no bearing on what I was about to encounter, and I used it to cure insomnia.

The second guide was to be Jacqueline’s son Fernando, a boy with rakish good looks, who at the time might have been 17. He attended a fine English school in Buenos Aires, and had spent summers on the family ranch in Patagonia, so he was at least qualified to be there from a geographical and family, if not an angling, perspective. Our third guide was a special fellow, and the only one of us with a Rio Grande address. He was a slight little man with a boyish face, taken to wearing the old-style Seal-Dri rubber waders, a woolen scarf, and eyeglasses held together at the temple with white tape. His name was Hector Mansilla. Hector was a waiter in the dining room at the local hotel. Owing to the fact that we wore a short, white, waiter’s coat to work each day, he had earned the nickname “saquito” or short coat. It was a delightful nickname, especially when Jacqueline said it by drawing out the short “a “ longer than it needed to be drawn out, then saying “quito” with great verve, like she had just announced the capital of Ecuador, and had thus won the final round on a quiz show.

That first season, fishing clients were hard to come by, which was not surprising given the fact that Kau Tapen was a first year operation, nobody knew about the fishery, and it was a million miles away from every world capital. Nevertheless, some intrepid clients made the two-day journey, and the first fishermen the lodge received after it opened for business were an aging Methodist minister and his brother.

In those days, to get from Buenos Aires to Rio Grande required a ten -hour trip with two connections, a rough enough day of flying, considering it occurred after one had flown all night from Miami. The last leg, a short hop across the El Estrecho de Magallanes from Rio Gallegos, was in a turbo prop of questionable airworthiness. Jacqueline was so concerned that her first clients would be delayed or confused that she sent Fernando to meet them and transport them back to the lodge while I scouted the river and Hector went back to work at the hotel. Fernando and the brothers arrived after dusk to find a candlelight dinner awaiting their arrival. While Fernando had been away, the newly wired generator shorted and caught fire. In a climate that gets little or no rain, only a perfectly timed cloudburst had doused the blaze and saved the generator hut and the lodge from total catastrophe.

The next day dawned clear and windy, and while the electricity was being repaired, the two brothers took to the river in the little Fiats. Accompanied in rotation by one of the guides, they fished what portions of the river they could reach by car. A grader had been previously employed to cut a road the length of the river, but due to the winding nature of the Rio Grande, in many places the road was hundreds of yards from the water. In that first season clients and guides walked from pool to pool, mingling with the sheep and carrying their tackle while the guides toted short-handled nets. Once they reached the river’s edge, they would tie on a wooly bugger, or some dark salmon fly and then swing it in the currents, hoping a big trout would eventually meet up with it at the end of the swing. Fishermen that were also concerned about being polite tourists would yield to the almost constant pressure from guide Hector, who was very vocal about his special fly he insisted they use, the “la campeona” (the champion), a long-shanked streamer with a wing of varying colored feathers, and a body of lead wire over peacock herl that Hector tied when he should have been bussing dishes at the hotel. On the third day of fishing at Kau Tapen, a miracle would occur that would rival Maradona’s World Cup goal two years later, a sea run trout miraculously impaled itself on one of Hector’s la campeonas while it was knotted to the tippet of the Methodist minister. After a splashy fight, Hector knocked the fish on the head. It was brought to the lodge where it was cooked by the grumpy chef. Jacqueline rang a little silver bell at the dining table and the grumpy chef’s wife served the trout with great ceremony. The brothers celebrated their great luck by burying Hector’s special fly up to the barb in the fabric of the dining room draperies, where it would hang for posterity. Then the brothers celebrated further by retiring to their quarters to wash their socks and undergarments in the bidet installed in their ensuite bathroom. Having not seen one in their previous travels, they had assumed it to be some fashion of in-room laundry. This was to be the last fish to be purposefully killed at the lodge, and so began the era of catch and release fishing on the Rio Grande.

While the guides, myself included, went to the river each day, determined to unlock the mysteries of the sea trout, Jacqueline and Betty busied themselves by cleaning the lodge obsessively. Jacqueline directed the staff, and wrung her hands as she looked longingly out the lodge windows hoping her paying clients would meet up with a trout. Meanwhile Betty, at 77, and barely a hundred pounds, cleaned like a dynamo in her pressed blue jeans. She washed the lodge floors on hands and knees, a process that took her three full days. After each fishing day, as their clients returned to the lodge Jacqueline would greet them at the front door, often in the black dark. Betty would ask, “How did my boys get on?” Then she’d usher them to the fireplace to get them out of the cold night air, as huge moths danced around the porch light and banged into the windowpanes.

One of the biggest challenges in that first year, aside from not really knowing much about the fish themselves, was dealing with the relentless Fuegian wind. I had been told before my arrival at Kau Tapen to expect high winds, but even as a boy born on the midwestern prairie I had no idea what fishing in 60 mile an hour winds would be like. The wind drove everything. It had influenced where the lodge was built, with a hill to protect it from the wind; it dictated how and where one parked the cars, (always into the wind, lest the doors be sprung by the gale), and it dictated the early and late fishing hours so that casting would be possible when the breeze was the least fierce. It also dictated where you hung your gear. Woe be the angler that left his lightweight waders on a hook outside the lodge. One left his Red Ball Waders on a hook and went inside for lunch. They blew off the hook, inflated like a brown nylon balloon, and were found draped over a three-wire fence, four miles downriver.

It is difficult to recall exactly the fishing that we had in those days on the Rio Grande, other than to say it was tough. I recall many weeks when the catch rates worked out to about one third of a fish per angler, per day. So if you were lucky you’d catch a trout on Wednesday. This made meals with the anglers a chore. We were tired, and they were tired. We were swinging our picks in a trout mine, and we weren’t finding many nuggets. The fish were so hard to come by that we were never able to establish any sort of pattern. We tried floating lines, intermediate lines, and of course we spent hours slinging heavy flies on heavy sinking tips, just hucking the whole mess up into the air for the wind to carry across to the far bank. We stripped it in, and did it again. This was well before the era of spey or two-handed rods, and loose fly line snarled in the wind on every cast. It was hard to envision that one would ever catch a fish, since the fishing process was so difficult.

The only thing we knew for certain in those days, was that in what has become to be known as “the magic hour” or the hour preceding dusk, a river you had fished all day long and appeared devoid of trout, would suddenly boil with brown trout as long as your arm–some as long as your leg. Hook ups in the daylight in those days were as rare as Argentina’s anti-inflationary policies. Nothing worked during the day, and if you caught a trout in the daylight hours, it was a gift on a rare, overcast day. But there were trout to be had in the darkness, and sleeping siesta became an important part of the routine in the early days of Rio Grande trout fishing. Given the southern latitude, the sun would not set until sometime after 11pm, and if you wanted to catch a big brown, you had to be on your game and ready sometime around 9pm with a fresh attitude and fresh barrel knots, for that was the time the wind would lie down and the big fish left the comfort of the sod cut banks. After a thousand casts with an 8 weight sinking tip, there was no better feeling in fishing than to find that your line had stopped swinging. Then you’d feel that dull, heavy, headshake somewhere beneath the flow. The take of one of those big browns was electric, if for no other reason than you had been so desensitized by casting, and casting, that just about the time that you felt virtually asleep at the wheel, you were hooked to your prize-this fish you travelled days and miles for was suddenly a living thing connected to you by fly line and brown Maxima, and then it is jumping, with it’s deep silver sides flashing in the moonlight.

The scene was always the same when those big trout were landed in the dark. You backed up on the gravel bank and slid the fish to the shallows and into the short handled net, and you marveled at this amazing creature, an odd combination of trout and salmon that seemed so out of place in a desolate land with sheep, and guanacos, and condors and flamingoes. With shaking hands you’d measure the fish and either sigh or gasp to find it was often comfortably over thirty inches; easily the biggest trout most people had ever seen, much less caught. I always had this shocked feeling every time I saw one of those big trout, whether I caught it or not. It was like seeing a live platypus or a zebra. You knew you were supposed to end up with this big fish, but it was shocking to finally have one in your hands, up close.

The trout would work it’s steel and turquoise colored gill plates as you scrambled to find your camera and then find the button for the flash, since by now it is ink well dark. After a flash photo the fish is slipped into the dark flow, and after time for your eyes to adjust, anglers and guides would begin the walk back to find the little fishing car. As you walked, you try to figure out the night sky and the lyrics crash into your head, “when you see the Southern Cross for the first time, you understand why you came this way,” and suddenly every minute on every airplane seemed worth it, and all you want to do is catch another one. More than anything you want to rush back to the lodge and tell the ladies that wait to meet you in the dark doorway that you have done so, because you know they’ll be so happy about it.

Kau Tapen, the modern era…..

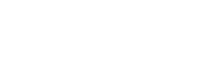

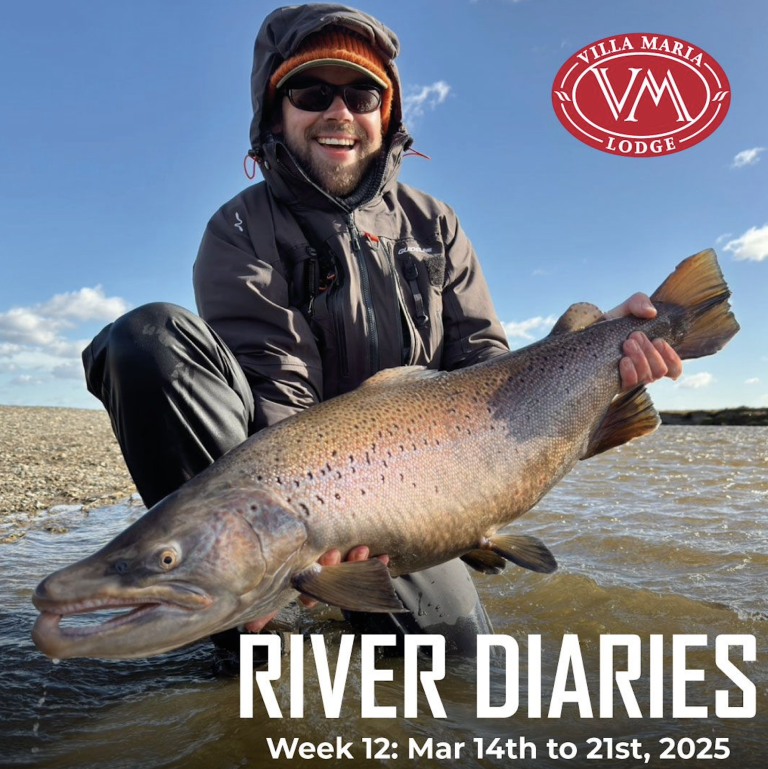

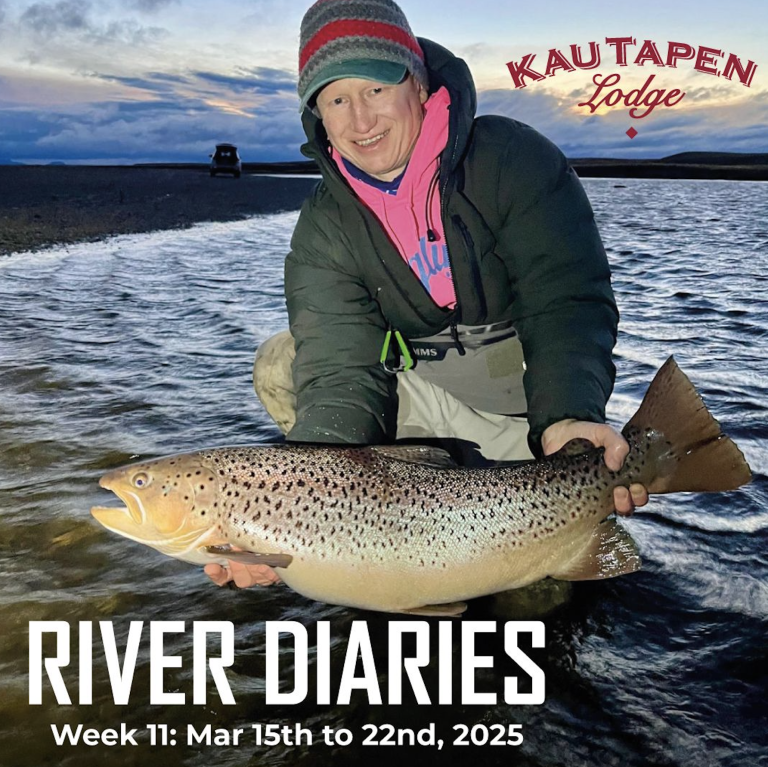

Following a rough beginning 30 years ago, Kau Tapen has had a storied record as one of the most exciting and interesting fishing destinations on the planet, and it has been visited by everyone from curious anglers to former Presidents. Anglers continue to travel to the lodge each year between late November and March with the hopes of meeting a big trout face to face on the Rio Grande. These days, the odds that they will do so are far better than they were back in 1984. The river is far more productive now than it was years ago, in large part due to the fact that Kau Tapen began the catch and release movement back in 1984. The run of trout has been studied over last six years, and has been determined to number about 75,000 trout, with staggering numbers of fish per mile. (In 2012 catch and release fishing finally became law in Tierra del Fuego) Last year, and indeed over the last decade, most anglers have averaged two or often three big trout per day. The average fish is still about 11 pounds, and the odds are very, very good that you will catch a trout of over 15 pounds during a week stay. Also, at least a fish or two over 20 pounds is landed each week. Trout up to 35 pounds have been landed from Kau Tapen, and over the years, lodge guests have been responsible for five IGFA world record catches.

Of course some things have changed too. Sadly, Betty is now gone, and Jacqueline is now a 75 year old grandmother that dotes on her grandchildren in Buenos Aires. Her son Fernando is a married father of two, and he is in charge of the Kau Tapen operation as CEO of his fishing company, Nervous Waters, the leading fly-fishing destination company in the world.

The lodge itself has been improved and added to over the years, it is now about 10,000 square feet with such modern amenities as wireless Internet, and a sauna/spa. There are beautiful guest rooms, with immaculate and stylish accommodation for up to 12 anglers per week, and meals are so amazing that guests routinely take photos of their plates with their smartphones. The Fiats are gone, and 4-door trucks whisk anglers to the river over a system of gravel roads designed to get anglers within a few steps of the best pools. Each day fishermen will visit between 4 and 8 different pools -plenty of water to choose from means better odds at catching the big one, and better angles for casting in the wind. The casting is easier too, the team of international guides at Kau Tapen has introduced all kinds of new tactics over the years, and today’s generation of spey and switch rods are the new norm for the Rio Grande, allowing anglers to roll the lines across the river easily, and keep a fly fishing, instead of tangling in the breeze. But the one thing that has not changed at Kau Tapen, is that electric feeling when a big trout takes your fly, 30 years later it is still thrilling. One more thing—fishermen are still encouraged to leave a fly in the curtains. It’s a tradition that has endured.

This article originally appeared in Sporting Classics in 2014